Rethinking the canonical design process diagram, and a call for beauty

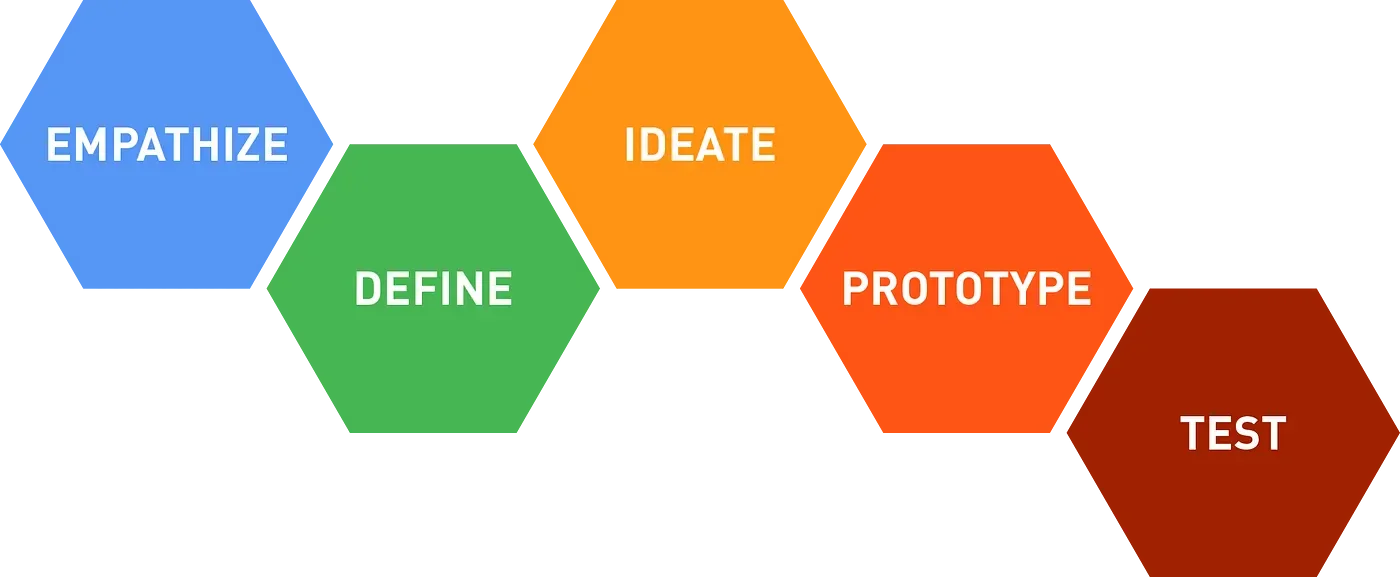

I’ve been reflecting on the canonical multi-hexagon diagram that illustrates the design thinking process. You probably know what I’m talking about, but for reference, here it is:

Canonical design process popularized by Stanford d.school

Stanford University’s d.school famously championed “design thinking” since its inception in 2004. It was borne amid the rise of the Internet, which was seeing its shift from something mostly used by computer nerds to technology consumed by the masses and changing the world. When I started my career in 1996, people thought of designers as people who “made things pretty.” Beauty was trivial compared to the exciting technological innovations and business opportunities, an afterthought after the business plan was developed and code written.

When I joined Netscape in 1996, the term “UX” had not been coined. Sure, the group I joined was named the User Experience team, and my manager’s title was Manager of Making Stuff Easy. In the digital realm, design was more about functionality, usability, and usefulness.

In 1998, I joined Yahoo! tasked with creating a human-centered design practice. Colloquially, I was part of the “Gooey” team, a play on the acronym GUI, which stands for Graphical User Interface. The Gooeys were graphic designers with HTML skills who could lay out the designs in code (this was before we had CSS). With no real budget, I hacked together one of the first usability labs during the dot-com era by threading a video cable over the wall through the ceiling from one conference room to another (this was before WiFi). One room was the participant room, and the other was the observation room. Before I joined Yahoo!, the product managers (called “Producers” since Yahoo! adopted a media model) designed the user flows and experience. They looked to the Gooeys to clean up their wireframes, skin the interface with color and type, and “make it pretty.”

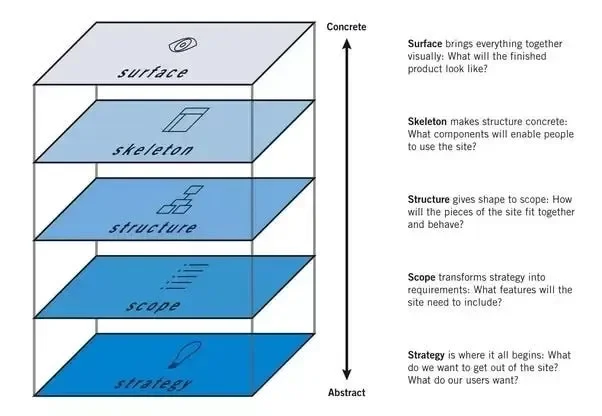

During this era, people interested in design educated themselves on human-centered design. They articulated and implemented processes to methodically gain an empathetic understanding of people and used that to inform and inspire product development. They taught stakeholders that design is more than skin deep. One of my favorite references is Jesse James Garrett’s The Elements of User Experience, whose framework endures even today.

The Elements of User Experience by Jesse James Garrett masterfully articulated how design is about more than how something looks

The early days of the Internet era were a land grab; companies wanted to build things quickly and make a lot of money without disciplined insight into what people needed or wanted. Designers were frustrated because they were brought in after product conception, ideation, and sometimes implementation with the task of prettying the interface. It was classic “putting lipstick on a pig” (it’s still a pig even with lipstick on). The work the design community did to teach stakeholders that design is about so much more than how something looks was significant and valuable. The earlier designers are involved in product ideation, conception, and structure of the offering, the better the design outcomes.

The UX profession owes a debt of gratitude to IDEO and Stanford’s d.school for articulating and popularizing the concept of “design thinking”, whereby product strategy, ideation, and conception are grounded in an empathetic understanding of human needs. Without that work, we would not be where we are today. It is more common now than ever for CEOs to recognize that design is as important as technology. Thanks to my former colleagues Jake Knapp and John Zeratsky who refined the design sprint process developed at Google by Charles Warren and productized it via their book Sprint and their forthcoming book Click, it’s easier than ever to engage in a design thinking process at any level for a company.

But design thinking is not “design making”. In my experience, this diagram does not accurately capture how design and product development are practiced in the real world. Furthermore, I’m not convinced that following the process as diagrammed results in better outcomes for the product. Here are my criticisms:

First, the diagram implies that design is a linear process. Yet, only when there is a commitment to continuous improvement does a product get better. As an operating partner at a venture capital firm, I coach CEOs to move away from linearity and the stress of needing to be perfect out of the gate. Don’t just launch something and move on to the next shiny feature or product. Instead, commit to continuous iteration. Those that do eventually get to the best answer. Design is a commitment to continuous making, testing, and iterating. By “making” I don’t just mean “launching”; “making” includes prototyping at any level of fidelity as well as launching.

Second, the diagram implies that empathizing is the first step of many in the aforementioned linear process. It’s a gate you go through to get to the next phase. “OK we did our exercises to build empathy, now let’s do the next step!” In practice, when the team stays connected to their hearts while they make, there will always be better outcomes because the product will resonate more with people.

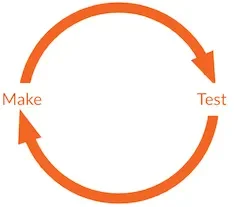

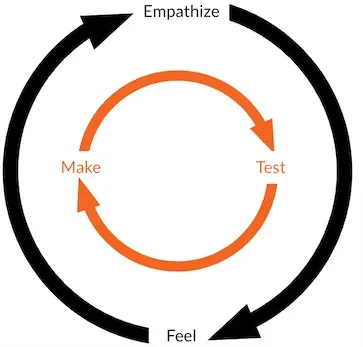

Any attempt to illustrate a robust creation process must capture the iterative aspect of making and learning — whether you’re engaging in an artistic endeavor or inventing new technology.

Making and learning iteratively are foundational to any creative endeavor

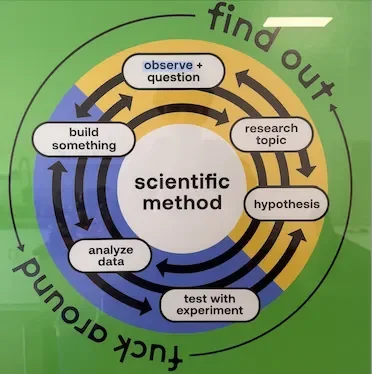

The startup Atomic Semi, which is working on a new way to fabricate semiconductors, cheekily captures their making process like this:

Atomic Semi’s cheeky product development process

In the context of inventing technology, “Test” (or “Find out” as Atomic Semi calls it) is usually a quantitative signal — Does it work? How well does it work and by how much based on our measures of success? In the context of making art, whether music, dance, visual art, or an exquisite meal, “Test” is a qualitative signal — How does this feel? How much does this move me, and in what way?

Design is an art and a science; it requires thinking and feeling. How might we make space for feeling when we design technology, and capture this in the design process? The iterative cycle of making and testing is held within a container of empathizing and feeling which are constant as we design. Feeling fuels empathy which inspires us as we make, and feeling allows us to gauge whether a design is successful from a qualitative, emotional, and energetic perspective. Empathizing is the heart; making is the hand and mind. Feeling is the qualitative; testing is the quantitative.

The ideal design process is a commitment to continuous making and testing, all within a container of empathizing and feeling. Heart, mind, and hand are integrated.

During his time at Apple, Bob Baxley recounted to me that the reason why Apple was so successful with design is because every senior executive was incredibly adept at expressing how a design made them feel, and they made space to talk about feelings during every design review. Wow!

What happens to designers when everyone in an organization engages in design thinking and it becomes “regular thinking”? I hope designers can return to making products usable and beautiful. At the strategic level, there may be clashes between design leaders and their counterparts in product management. I’d love to see these designers move into product leadership or general management and run the cross-functional team, as Audrey Liu does at Lyft. Designers who remain designers and keep their seats at the table can use their unique skills to make ideas tangible. They can influence executive stakeholders by bringing ideas to life and helping them understand what the potential outcomes of their decisions might be. (This is ultimately the answer to the question “Designers finally have a seat at the table. What do we do next?” BTW you have to earn that seat, it’s not a given.)

There is no shame in focusing on form and function. Both are strategic, but God is in the details. We need beauty in the world now more than ever to return us to the qualities that make us the best versions of ourselves: humility, grace, compassion, kindness, and love. Somehow the UX/design profession has come to a point where people feel like if they’re not working on design strategy, they’re not advancing in their career. Organizations must ensure a career path for those who focus on their craft. If beauty is beneath you as a designer, who else will champion it?

(This post was originally posted on Medium on March 6, 2025)